As a sci-fi fan, it would be

remiss of me in the final few hours of 2017 not to somehow honor the 40th

anniversary of the premier of Star Wars.

There is little I can add to the recognition, but I do have one story that

perhaps illustrates the power of the phenomenon to those too young to remember

a world before George Lucas’ blockbuster movie.

When the film debuted in May

1977, I was not immediately taken with the hype. Star Trek was my main sci-fi interest and I regarded Star Wars as an over-produced, genre-destroying,

corporate monster. I waited over a year before finally giving in to peer-pressure

and got my dad to take me during one of our weekly divorced-dad weekends in

June 1978.

Now, I hasten to add that Star Wars had been playing at our local

multiplex, Cine 1-2-3-4-5-6 (yes, that was its name) at Northway Mall in Albany, NY, since May 1977, so

it was playing for a full year before I saw it — and the theater was still

packed. Let that sink in for a moment. Star

Wars played at theaters continuously for over a year. It’s impossible to

imagine any film doing the same thing today.

|

| The old Cine 1-2-3-4-5-6, here upgraded to Cine 10. Demolished in May 2007 (cinematreasures.org). |

I was looking for any reason not

to like the movie. When an imperial officer used the word “sensors” early in

the film, I leaned over to my dad and said that was used in Star Trek. My dad shushed me and told me to give it a

chance. By the time Luke Skywalker fired up his lightsaber for the first time, I

was hooked. As though bound by quantum entanglement, I remain so today.

The backstory of an awkward young

man with limited prospects who hates his life rang true with a lot of kids, and

still does. Luke Skywalker’s coming-of-age is what gives the film its heart and

helps it rise above what Alec Guinness described as the “banality” of the

dialog in the script. My father, despite being an ex-marine himself, got a bit motion

sick during the Death Star run. Nevertheless, having grown up with Buck Rogers and Flash

Gordon serials, he recognized the similarities which Lucas used in

creating the film’s overall structure. By building on the work of the previous

generation, George Lucas created a film that attracted young and old alike.

The backstory of an awkward young

man with limited prospects who hates his life rang true with a lot of kids, and

still does. Luke Skywalker’s coming-of-age is what gives the film its heart and

helps it rise above what Alec Guinness described as the “banality” of the

dialog in the script. My father, despite being an ex-marine himself, got a bit motion

sick during the Death Star run. Nevertheless, having grown up with Buck Rogers and Flash

Gordon serials, he recognized the similarities which Lucas used in

creating the film’s overall structure. By building on the work of the previous

generation, George Lucas created a film that attracted young and old alike.

Hey, I’m a Believer!

I walked into the theater a

skeptic and walked out into the hot June night a hard-core, rock-solid, Stars Wars fan. I quickly joined the fan

club, got the Kenner figures, got the models, got the soundtrack, and got the

books. The only books at the time, however, were the novelization of the film

(1976) and Splinter of the Mind’s Eye

(1978), both by Alan Dean Foster, who also wrote Star Trek Log One, which I cover in another article (see link).

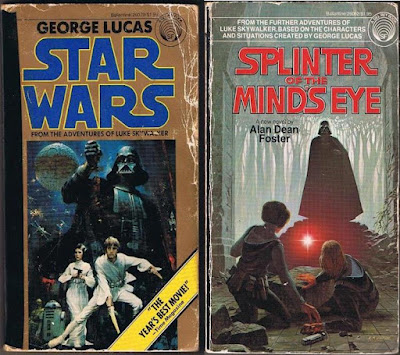

|

| Book covers to Star Wars and Splinter of the Mind’s Eye (original copies, author’s collection). |

I still have those books (see above). The

gold cover of the movie novelization is wrinkled from when my brother and I

fought over reading it in 1978. Some pictures later fell out, which

I saved and put back. The binding fell apart in the 1990s and it is now held

together by electrician’s tape. The dog-eared pages are now yellowed and

stained. I took them with me wherever I moved throughout middle school, high

school, and college. I probably haven’t read them in 20 to 25 years, but I could

no more get rid of them than I could sever a limb or a memory.

With the books came the music. I

played the 8-track of John Williams’ soundtrack almost daily. I also got the

single with the disco version by Meco. That single was huge and turned up on

TV, radio, and in ads. It even helped inspire me during my runs that summer of

1978 (as referenced in my short story “I Now Know Why Salmon Swim Upstream”).While I

still have Meco’s singles for The Empire

Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi,

which I bought at the time of the films’ releases, I long ago lost the 45 for

the first film — which brings me to the most interesting part of my tale.

|

| Meco's 45s for the Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi (author's collection). |

After the divorce in 1978, mom

sold the house and we moved into a much smaller brick row house. By the summer

of 1980, I was working for my mother’s one-woman cleaning service. She had a

number of customers in an exclusive upscale apartment/condominium complex

called Oxford Heights. She was in high demand because she provided complete

service, including windows and laundry. I was paid $5 an hour (about $15 at the

time of this writing), which was a pretty respectable wage for a 15 year old. Despite

the high pay, I loathed the work. It was boring and tedious and my Sicilian

mother was a stern taskmaster. Instead of swimming and going to baseball games,

I spent the summer stinking of bleach and folding other people’s underwear. My mom

worked me eight hours a day, five days a week and . . . wait. Wasn’t this

supposed to be a Star Wars story?

Gold . . . Everywhere, the Glint of Gold . . .

One day during that summer of 1980,

while cleaning the apartment of a young couple by the last name of Fenton, I

was vacuuming the hallway leading into the bedroom when I caught a flash of

gold out of my eye. I looked up and saw a gold record. An actual, honest-to-goodness,

gold record awarded for at least one million sales. The light reflected off it

like a disco ball. I looked closer and saw it was for Meco’s Star Wars theme single.

I think I almost passed out right

there.

I called to my mother and asked

her about it. My mother, who never saw the movie, responded nonchalantly that

the husband, Mike Fenton, who worked as a casting agent in New York City, was a

friend of Meco who gave it him. For a moment, amid all the family dysfunction

and the grind of a lost summer, I was connected to a phenomenon — if in only in

the most tangential of ways. I glimpsed

behind the curtain and beheld the face of Oz.

On a cosmic scale, considering

the present age of the universe of some 13.8 billion years, 40 years is so

small a percentage that barely a measurable amount of time has passed between

1978 and 2018. So, in some way, it is still June 1978 and I am still at that

theater in Albany, NY. Indeed, every time I watch Star Wars I am transported, albeit briefly, back to that one moment

in time and space. My father is still alive, I am still young, I am still sitting

on the edge of my seat, and I am still waiting for the movie to begin.

It seems like it was only

yesterday.