by G. Jack Urso

If someone succeeds in provoking you, realize that your mind is complicit in the provocation. — Epictetus, Greek Philosopher.

Photograph of a fake highway sign by Michigan Technological University students in 1984. Also applies to Houghton, NY (copyright John Marchesi).

Houghton College

is in the middle of nowhere, and you have to bring your own nowhere.

When I attended

Houghton College in the 1980s, the small, isolated Conservative Evangelical

college community in Alleghany County had an insular provincialism that

provided a sort of safe haven from the world for religiously indoctrinated

youth experiencing their first real freedoms as adults, myself included. There

were few computers, poor radio reception, poor TV reception, and no cable TV. Students

were required to sign “the Pledge,” a contractual agreement that said the

student would not dance, drink, do drugs, have sex (at least get caught), go to

chapel, etc. Going to the movies on Sunday was also verboten, but things really

loosened up in 1983 when they began letting students use playing cards.

When I attended

Houghton College in the 1980s, the small, isolated Conservative Evangelical

college community in Alleghany County had an insular provincialism that

provided a sort of safe haven from the world for religiously indoctrinated

youth experiencing their first real freedoms as adults, myself included. There

were few computers, poor radio reception, poor TV reception, and no cable TV. Students

were required to sign “the Pledge,” a contractual agreement that said the

student would not dance, drink, do drugs, have sex (at least get caught), go to

chapel, etc. Going to the movies on Sunday was also verboten, but things really

loosened up in 1983 when they began letting students use playing cards.Suddenly, Perkins

We told him about how our land was stolen and our people were dying. . . . He shook our hands and said “Endeavor to persevere.” We thought about it for a long time, “Endeavor to persevere.” And when we had thought about it long enough, we declared war on the Union. — Lone Watie, The Outlaw Josey Wales.

Professor Rich Perkins,

a sociology professor, was bothered by a recent op-ed I wrote in my weekly column,

“Pandora’s Box,” in the Oct. 9, 1987, issue of The Houghton Star titled “War and Peace” which addressed the

question of whether Christians should serve in the military. A hypothetical

situation regarding an invasion of the United States by the Soviet Union was

proposed in an exercise in values clarification. I asked, what should be the

Christian’s response?

“Would

I kill to liberate? . . . No, I would not. Christ, if you recall, was born in

an occupied land. . . . Christ did nothing to further the zealots’ cause.”

I identified as

a pacifist and stated that I thought, based on the New Testament, Christians

should not serve in the military. My opinion was that unlike personal

self-defense, joining the military is proactively seeking out the opportunity

either to kill or to support the killing machine. While it may be true that

there are no atheists in foxholes, there is no God either. War is an act

entirely of our own creation. We own war — not God nor the devil. So, military

service, even under an occupation, seemed to me to be incongruent with the

teachings and life experience of Jesus.

Professor

Perkins, who served in the army during the Vietnam War (I believe as a lieutenant),

and being a man of faith, took umbrage at my assertions. As a draft-era

veteran, he didn’t have much of a choice except get an academic or medical deferment,

dodge it, or serve. In response, rather than writing a letter to the college

newspaper to bitch about me, as dozens did that year, Perkins instead choose to

approach me in line at Big Al’s while I was waiting on an order of wings.

I knew of

Perkins, everyone did. He was one of the most well-liked professors on campus,

but I don’t recall ever having spoken to him before, let alone taken a class. So,

I wasn’t a student of his, I didn’t live in the commune (more on that later),

and I didn’t mention him in my column, so I wasn’t sure why he felt he needed

to approach me.

He seemed a bit hesitant.

I could tell this was a sensitive issue for him. Perkins must have seen his

share of combat in the war, maybe lost some comrades, and my column probably

kicked up some old dust. He briefly explained the moral quandary of his

generation and ended with a plaintive, “Well, that’s all I wanted to say.”

I was a little

confused. I did not mention Vietnam. I proposed a hypothetical regarding a Red Dawn-type scenario where we get

invaded, not where we do the invading (as in Vietnam), but apparently the

discussion of the morality of the faithful participating in the war machine

struck a nerve. I muttered, “Um . . . OK. Whatever,” and took my order and

left. I had a couple other words in mind, but I felt it better to err on the

side of respect.

It was a rare

moment of restraint for my younger self.

It probably

struck Perkins as though I was being arrogant and didn’t give a damn, which

actually was sort of true. Nevertheless, it was obviously a sensitive issue for

him. Typically, impromptu public debates accomplish little more than just

exercise egos. Besides, I wasn’t interested in debating, proselytizing, or

changing anyone’s mind. I just wanted to have my say, I had my say, and if that

bugs you, that’s on you. Let me eat my wings.

The

Communards

If any man despises me, that’s his problem. My only concern is not doing or saying anything deserving of contempt. — Marcus Aurelius, Roman Emperor.

Perkins was in

charge of one of two “communal” off-campus houses, one for women and one for

men. I use “communal” in quotes because it wasn’t really a commune; it was more

of a cooperative living experiment — which, actually, I guess is sort of the

definition for a commune, but I digress. The residents were generally all

like-minded liberal Evangelical Christians, though a few conservatives may have

been included to balance things out. Nevertheless, it was largely liberal in

orientation. Though to be clear, a liberal Evangelical Christian in the 1980s

would probably be considered a moderate conservative today.

The emphasis of

the community, if I recall correctly, was on building consensus among the

residents with house activities, group meetings, group hugs, and fundraising

for the Saul Alinsky Scholarship Fund.

I’m only joking

about one of those, of course.

Unlike other on-

and off-campus housing, where you got a place if there was a vacancy,

admittance at the commune was selective, like a fraternity or sorority.

Students had to apply for admittance and were voted on by the other residents.

I believe this required either a majority or unanimous vote, but either way

this struck many as not quite as egalitarian as the commune’s values laid claim

to.

Due to the

collective nature and liberal politics, the residents were sometimes referred

to as “communards,” more so after the eponymous 1980s’ band than the members of

the 1871 Paris Commune, though it kind of worked both ways. Despite my liberal

beliefs, I was more of a “Christo-Anarchist,” which actually is a word. I did

not invent it. I only discovered it years later, though I admit it probably is

a good thing I did not find my “label” back then. Christo—Anarchism is a

rejection of hierarchical authoritarian structures, both state and religious,

with an emphasis on the Sermon on the Mount for its core principals. At the

time, that pretty much defined my worldview. Like a malignant mutation, we

spring up spontaneously at random, produced by the very system we criticize.

Interestingly,

my biggest conflicts on campus were not with the conservative Christians, who,

apart from some passive-aggressive behavior and letters to The Houghton Star, generally ignored me, viewing me with little

more regard than they would a feces-throwing monkey at a circus sideshow.

Rather, my conflicts were often with the liberal Christians who thought my

antics were counterproductive, unChrist-like, and downright rude, which

actually was the point, if I had one at all. Anyone looking for a method to my

madness, I quote Minimalist composer John Cage, “I have nothing to say and I am

saying it.”

Interestingly,

my biggest conflicts on campus were not with the conservative Christians, who,

apart from some passive-aggressive behavior and letters to The Houghton Star, generally ignored me, viewing me with little

more regard than they would a feces-throwing monkey at a circus sideshow.

Rather, my conflicts were often with the liberal Christians who thought my

antics were counterproductive, unChrist-like, and downright rude, which

actually was the point, if I had one at all. Anyone looking for a method to my

madness, I quote Minimalist composer John Cage, “I have nothing to say and I am

saying it.”Despite my

disagreement with certain philosophical elements of the commune, I remain

friends with several former residents, who I regard as some of the better

representatives of the faith.

In some ways,

the campus conservatives and the communards were two sides of the same coin,

both embracing hierarchical authoritarian structures with value systems they

thought were inherently superior to each other’s. My belief was simply, “A pox

on both your houses.” Consequently, despite sharing liberal beliefs, my

anarchism often found me ideologically at odds not only with the campus

conservatives, but also sometimes with the communards, and occasionally with

Prof. Perkins himself.

Anarchy

in the Alleghenies

Your boos mean nothing. I’ve seen what makes you cheer.

— Rick Sanchez, Rick and Morty.

I previously

have discussed my antics as I blew through my college career in “A Liberal in the Land of Canaan,” “Blond Jesus: The Holy Hitchhiker,” “Jesus Drives Stick,” “Integrity is a Four-Letter Word,” and “Year of the Dog.” Such modest efforts included grabbing

the mike after a couple sets with the campus cover band “The Pledge” in the

chapel for an impromptu protest against the Selective Service, or sitting down

during the National Anthem during a basketball game, or testing a rich,

new-found convert’s claim he no longer cared about material goods by taking his

Mazda RX-7 for a transmission-grinding joyride.

I ended up with

my previously mentioned column, “Pandora’s Box” through a bit of subterfuge.

The editor of The Houghton Star was elected

through a popular vote. After the winner for my senior year had been announced,

some supporters told me they stuffed the ballot boxes in his favor. Actually,

they told me about it while we were smoking weed in the laundromat in town.

Their candidate, a communard, never worked for the paper, while the “loser” had

worked tirelessly the past three years. Usually, I wouldn’t have cared, but it

rankled my sense of fair play.

I ended up with

my previously mentioned column, “Pandora’s Box” through a bit of subterfuge.

The editor of The Houghton Star was elected

through a popular vote. After the winner for my senior year had been announced,

some supporters told me they stuffed the ballot boxes in his favor. Actually,

they told me about it while we were smoking weed in the laundromat in town.

Their candidate, a communard, never worked for the paper, while the “loser” had

worked tirelessly the past three years. Usually, I wouldn’t have cared, but it

rankled my sense of fair play. Also, all they had was dirt weed.

I “casually”

informed a friend on the student senate about my encounter. To his credit, he

kept the pot-smoking part out of it when he told the dean. However, before that

happened, I extracted a promise from the loser that if I could get a new

election, and she won, she would have to give me my own column. She thought I

was nuts, but shook on it and kept her promise when she won the reelection.

This probably didn’t endear me much to Perkins or the commune, but right is

right, though I did obviously use it to my advantage. The title of my first

column was “God is Dead.”

Along with a

couple other classmates, we started a band called "China Blue," for which

we would write and play all our own pretentious music. We liked the name

because it had an artsy-fartsy ring to it that would appeal to the avant-garde

on campus, but primarily because it was the name of a prostitute played by

Kathleen Turner in the film Crimes of

Passion (1984) and we got some kind of vicarious pleasure seeing the name

publicized in various forms on campus.

I helped set up

the first chapter of Amnesty International on campus, and served as

co-president, though all credit goes to my friend Mark for proposing it,

getting it going, and doing the heavy lifting. Among the news we’d get from

Amnesty International were reports of weapon sales and transfers, like

landmines. In addition to solidifying my pacifism, this sparked an interest in

the arms industry which eventually led me to a 25-plus year career as a

freelance defense consultant specializing in tracking weapon development,

deployments, and sales.

In 1985, Ron

Sider, founder of Evangelicals for Social Action, and the author of the

influential book, Rich Christians in an

Age of Hunger: Moving from Affluence to Generosity (1979), appeared on the Buffalo

Suburban Campus of the college with a panel of Buffalo-area pastors for a

lecture about the new challenges for the church in the 1980s. Sider’s book was

must-reading and given his reputation on the cutting edge of social issues as a

Christian, I thought it curious that he did not mention HIV/AIDS or

homosexuality at all in his lecture. It was 1985 and it was the hot topic of

the day, but not a word on it from Sider. So, during the Q&A I asked them,

and Sider specifically, what the church was doing to reach out and minister to

this group of people. It was a cheap trick because I knew the church wasn’t

doing squat, but I was curious to see how he would answer it.

The audience

groaned and mumbled while the girl next to me covered her face and shrank down

in her seat trying to hide from view. I wasn’t gay, but I knew a few of my

classmates were, and I knew someone who died of AIDS. I listened carefully to

what Sider said, and what he didn’t say. He fumbled about for a minute, but

couldn’t come up with anything except that he

heard a church in Philadelphia was “doing something.” Thanks Ron. I can see

you were way ahead of the curve on this. It was clear this just wasn’t on the

liberal Christian guru’s radar at the time. This was probably the point when my

liberalism began to give way to anarchism.

It was a loaded

question of sorts because I knew one of the pastors on the panel excommunicated

a man in his church over homosexuality. By the way, I am not dredging up an old

grievance I never spoke about publicly at the time. I actually wrote about the

incident in my column for The Houghton

Star in 1987 (see image at left).

In 1987, along

with another couple like-minded classmates, we campaigned for, and won, the

leadership positions of the campus chapter of Evangelicals for Social Action

(ESA), a nationwide organization founded by Sider and the usual stomping

grounds for the communards. We had never worked with ESA before, but thought

the group could widen its appeal, and apparently so did enough of the members.

Afterwards, there was a bit of an exodus as some who supported the previous

leadership left the group rather than work with us, but it clarified who was

serious about ESA.

The ESA picture in the 1988 Houghton College yearbook. I insisted that it be taken in front of the urinals in the campus center men’s room as a symbolic gesture.

Once, local

Congressional Rep. Amo Houghton (related to the college’s founding family) invited

a Contra to the college to speak in hopes of getting support of funding for his

organization, then involved in a war against the Communist Nicaraguan

government with CIA assistance. The student senate president, and a resident of

the commune, asked me to join him in aggressively questioning the Contra about

his group and the Iran-Contra affair.

We attended both

of the two Q&A sessions, sitting together in the packed rooms asking

complex, multipart questions which challenged the Contra’s weak English

language skills. It was a cheap trick to put the Contra at a disadvantage, but

after trying an end-run around the Congress to fund a revolution the first

time, they should have brought their A-game for the second attempt. The Secret

Service eyed us suspiciously in the first session (the fact that the Black

student senate president was a British citizen with an accent to match probably

caught their attention). During the second session, the SS had enough and cut

the hour-long meeting thirty minutes short. Amo Houghton later withdrew his

support for funding the Contras.

Somehow, I

managed to land a job working night security on campus. Frankly, I was as

surprised as anyone else when they hired me. My job was to check that doors

were locked, walk around campus looking for trouble, and let students into

their dorms after curfew. This was great as I got to know every girl who stayed

out late and also got to raid the leftovers in the cafeteria. After that, I

would swing by the new guys’ dorm at about 1 am and roust a couple freshmen I

knew to borrow their comic books and argue campus politics with them.

During my

security guard shifts, I began leaving snarky, wiseass, anonymous comments on

the bulletin board outside the campus center post office criticizing various

religious beliefs. Those who disagreed began leaving responses and it was soon

dubbed, “The Wittenberg Board.” After a couple months, the whole thing started

to get out of control with decidedly unChrist-like anger in the responses

growing in number each day. Satisfied I had accomplished my goal, I stopped,

but the chaos continued without me.

I also ran afoul

with some of the locals who understandably had nothing else better to do in a

one-horse town where you had to bring your own horse and your own town. One

night, a pick-up with a trio of townies saw me and began harassing me. This

actually wasn’t my first encounter with Jughead, Gomer, and Goober, as I called

them. Typically, they only had the courage for a passing insult, but tonight

they seemed ready for something more.

After listening

to their shit for a couple seconds, I did what any Sicilian would do knowing he

was alone, outnumbered, and on foot — I gave them the finger and a defiant

“FUCK YOU!” Notably, this was in front of the only church in town. Gunning the

engine, they came after me, making a U-turn, crossing the medium, and driving

over the sidewalk in pursuit. I took off down the street and managed to lose

them in the trailer park, which, I have to admit, I was amazed when that

actually worked. I banged on the nearby door of a bodybuilder friend for help who

came out saying he always knew they’d come after me some day. He had a “talk”

with the townies and I didn’t see them for the rest of the semester. This

incident, and others like it, was reported in the college newspaper April 22,

1988 (see image at right).

After listening

to their shit for a couple seconds, I did what any Sicilian would do knowing he

was alone, outnumbered, and on foot — I gave them the finger and a defiant

“FUCK YOU!” Notably, this was in front of the only church in town. Gunning the

engine, they came after me, making a U-turn, crossing the medium, and driving

over the sidewalk in pursuit. I took off down the street and managed to lose

them in the trailer park, which, I have to admit, I was amazed when that

actually worked. I banged on the nearby door of a bodybuilder friend for help who

came out saying he always knew they’d come after me some day. He had a “talk”

with the townies and I didn’t see them for the rest of the semester. This

incident, and others like it, was reported in the college newspaper April 22,

1988 (see image at right).I could go on

with other examples of my misspent youth, but something about the statute of

limitations comes to mind.

Good times . . .

Good times.

Professor Perkins’ Pernicious

Pupil

Whatever happened to the American Dream? You’re looking at it. It came true. — Edward (The Comedian) Blake, The Watchmen (my senior yearbook quote).

The Spring of

1988 found me needing just one course to graduate, Intermediate Spanish II. Two

years of a foreign language were required and as I had failed one semester and

barely passed another, what should have taken me two years instead took three. It

was one of those archaic liberal arts requirements and had absolutely nothing

to do with my major, Broadcast Communications, or my minor, Literature. I did

nothing with it. I cannot speak a word of it today. It was a complete and total

waste of time and money that would have been better spent training me for my

career.

But hey, can’t

hold a grudge, right?

After the events

recounted in “Integrity is a Four-Letter Word,” instead of

transferring to a college back home to take the course, I decided to stay and

finish out Spanish with the instructor I knew and completely forget. Better the

devil you know then the devil you don’t I figured.

For the other

course, I decided to finally give Prof. Perkins a shot and take Social

Stratification, a critical look at the interrelated dynamics of aspirations, class,

and the economy. The standard class size

was about twenty-four students, and the class was full. Only some were

Sociology majors. Others came from Business, Communications, Education, etc.

Perkins had a rep on campus for being one of those professors you just “had” to

take a course with, if just for the experience.

Both my classes

were between 1 pm and 4 pm Monday through Friday. Since I can be a bit

obsessive-compulsive in a slacker sort-of way, I spent every morning listening

to the rock operas Tommy or Quadrophonia by The Who, and smoking a

joint, often with another student hanging out between classes. As I lived in

Jack House (named after a former coach, not me), an off-campus house whose

houseparent was a single guy who worked in admissions and was away traveling

most of the time. Consequently, with little supervision, it became pretty permissive

regarding smoking pot and having girls over.

When out and

about, I had my ever-present Walkman and usually one of the Violent Femmes’ tapes

popped in and ready to go. The folk punk band’s anger and angst-ridden

critiques of society always set me in the mood for discussions in class.

The

Game of Class — Everyone Plays It, so Few Have It.

Let me tell you about the rich. They are different than you and me. — F. Scott Fitzgerald (1926)Yes, they have more money. — Ernest Hemingway (1936) (Gilbert & Kahl, The American Class Structure, p. 84.)

For one of our

final papers in Perkin’s class that semester, we were to write an analysis of

our participation in a game in that mimics the dynamics of moving between

economic classes. I forget what the name of it was, so let’s just call it The Game of Class. Perkins reserved

space in the smaller auditorium where communications classes or the theater

group met. Three large tables were set up. Perkins, standing behind the podium,

explained the rules of the game. I may be foggy on some of the details, but the

general thrust of the game is as follows.

Each of the

three main economic classes would be represented by wooden blocks in the shape

of a yellow triangle for the upper class, a green square for the middle class,

and a red circle for the lower class. The goal of the game is to move through

the classes, from lower to upper. Each class required a certain number of blocks

to get in. I forget the cost, but let’s say it was one red circle to get into

the lower class, two green squares for the middle class, and three yellow

triangles for the upper class.

To start, as I

recall, everyone was given the same number of blocks, but a random selection.

So, some might be “born” in the upper class without having really done anything

to get there. Staying there, however, was another matter, but we’ll get to that

in a moment.

There were two

sessions of play, the negotiation session and the committee session. The first

was the negotiation session during which one could barter and trade to get more

blocks. Someone might trade you three red circles for one yellow triangle, but

the exchange rate wasn’t fixed. It differed from person to person and changed

as the number of members in each class rose and fell. Sometimes, the availability

of blocks to trade diminished as players held on to them for their own

advancement, or to stop others from advancing. One could barter anything, not

just blocks, such as promises of voting support during the committee sessions

and conspiring to get someone kicked out of a leadership position in the group.

Anything and everything were on the table. This might go on for five minutes.

After the

negotiation session there was the committee session. In committee, the members

of each class could make rules voted on in proper democratic parliamentary procedure.

A president and other officers could be voted on. A constitution of sorts for

each group was made up and voted on as well. This would go on for about another five minutes or so.

Then, in the

very next session everything from the previous session could be overturned as

new members join and old members change alliances. A coup d'état could take place and the old

order overthrown and a new constitution written. It quickly became apparent

that little could get done as the dominant personalities jockeyed for position

and influence. I don’t recall if one could get voted out of a group, but people

could lose their blocks and go down a class, conspire to isolate a player,

refuse to barter with them, and essentially prevent them from obtaining

influence in their group.

After a couple

rounds, it was apparent that the cycle of negotiation and barter and committee

meetings soon became not just the focus, but the whole point of the game — to

create a self-sustaining perpetual motion machine of pointlessness. That actually

probably was the point, but I also observed that there was a lot of

backstabbing and lying and hurt feelings taking place.

It reminded me

about having been required to play the game Diplomacy

in Dean Massey’s Western Civilization class as a freshman. Diplomacy is a bit like the game Risk, but set in Europe during World War I. To move, players have

to write orders and get the support of allies, so influence, not luck, is how

the game is played. One nation is not strong enough to win on its own, but only

one nation can win the game. As with Prof. Perkins’ Game of Class, there is a negotiation session during which allied

players coordinate their moves to defeat other players; however, it is just a

matter of time before someone backstabs you. I remember how all the games

dissolved into arguments, hurt feelings, and occasionally tears.

As it turned

out, Dean Massey had never played the game. Considering all the melodrama, I

wonder how he would have done. Likewise, I wondered how Perkins might do if he

had to play his own game. Well, even feces-throwing monkeys at the circus get

tired of being objects of other people’s entertainment and I just about had

enough of being a lab rat, so I sat down.

I picked a spot

in the middle of the room strategically located between the three tables and

sat on the floor. Everyone would have to walk around me or over me, acknowledge

me or ignore me, but they would have to deal with me. I thought about putting

on my headphones and listening to the Violent Femmes, but concluded that would

be more disrespectful than just sitting down in the middle of everyone’s way. I

didn’t have to go full asshole. Half asshole would do just fine.

|

| An anonymous ad in the college newspaper. |

Prof. Perkins

gave me a look from his perch behind the podium. It was the “Oh God, what is he

going to do now?” look I had become acquainted with. I did a sit-down protest

at a basketball game when I sat down during the National Anthem (see “A Liberal in the Land of Canaan”), so I was

pulling out an old trick. As I learned, when used at the right time, passive,

non-violent, non-action can be very, very provocative.

The other

students tried to ignore me at first. Some had a few terse comments about me

messing things up. Some asked me why I was doing it. I simply answered, “I

don’t wanna.” Expecting some extended anarchist diatribe from me, this

frustrated them even further.

I sat there

alone for a session or two until a couple students joined me. Then, after

another session, a few more joined us. At this point, I probably did shout some

Marxist slogans, primarily Groucho (“I refuse to join any club that would have

me for a member”) and tossed in a “Viva la Revolution!” with my fist in the air

just for good measure. That was probably the only phrase in Spanish after three

years I could remember, though I probably picked it up from a Speedy Gonzalez

cartoon.

A snapshot of my personality and politics not long after graduation on WQBK-1300 AM. I may have mellowed out a bit since then.

Towards the end,

about half the class joined me. The students who continued to play were spread

across the now-sparsely occupied tables. With fewer participants, the last couple

rounds were essentially lame duck sessions and the game slowly ground to a halt.

Then, the bell rang and class was over.

As everyone

meandered their way out the door, I got up off the floor, grabbed my books, and

snapped on my headphones. Prof. Perkins leaned his long, lanky arms over the

lectern and gave me a look that was both exasperated and amused, but mostly

exasperated.

“This won’t

affect my participation grade will it?” I asked rhetorically as I walked by and

turned on the Violent Femmes without waiting for an answer.

In

Passing

“The only way to win is not to play.” War Games (1983)

In my paper,

regarding my analysis of the game and the social class structure, I concluded

by quoting from the film War Games

(1983), “The only way to win is not to play.” This has continued to embody my

attitude towards class and social stratification, though I’m not quite sure

that was the lesson intended by the game.

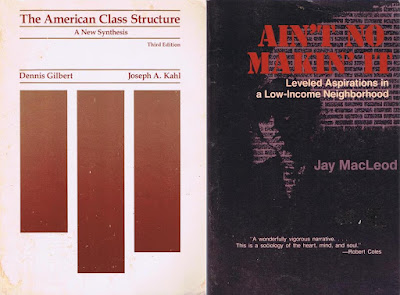

I still have my

textbooks from the class, The American

Class Structure, by Dennis Gilbert and Joseph A. Kahl, and Ain’t No Making It, by Jay MacLeod. I

have read them periodically over the past 34 years. Admittedly, I was not much

of a student, and my face lost among the thousands Perkins taught in his

lifetime, but I doubt many of them kept the books or reread them.

Looking at our

past is often through rose-colored glasses. As is the case with trips down

memory lane, I am recalling events through my own singular perspective, which

may be different than some of my old classmates’ recollections. I have

certainly mellowed over the years and am no longer the thin, scruffy,

long-haired neo-hippie I was so many years ago, though largely my opinions

haven’t changed.

I know it sounds

like I have been critical of Prof. Perkins, but he gave me space in class to be

me and explore my ideas. An old classmate recently reminded me how my debates with

Perkins would take up most of the class. It made me remember how patient he must

have been.

Every once in a while, I get a student all fired up who wants to

spend the entire class debating their idea du jour, much like I used to do. I always

remember Prof. Perkins, take a breath, let them have their say, and then explain

why I’m right.

Maybe I didn’t

change all that much after all, but I like to think that would have pleased

him.

Richard B. Perkins,

1943-2022.

● ● ●

Note: Since the original publication of this story, Houghton College has since been renamed Houghton University.

Enjoyed the piece. Having gone through a critical thinking rebirth in college myself, I can relate to your overview of your experience at Houghton - well done. I think Prof. Perkins would be pleased and proud.

ReplyDelete