by G. Jack Urso

In a world of

Frostys, Grinches, and Rudolphs, A

Charlie Brown Christmas stands out as one of the very few Christmas

specials that include scripture in its dialog directly related to the birth of

Christ. We see this in Linus’ recitation of the annunciation to the shepherds

from Luke, chapter 2. The overall plot, a critique of the commercialization of

the holiday, tapped into mid-century Western angst in the period of post-war

prosperity. Together, these two themes intertwine to elevate the animated

special into an almost spiritual experience.

I was born in

late 1964, so A Charlie Brown Christmas

was one of the first animated Christmas specials I can remember watching, being

planted down in front of the TV at the age of one with my siblings to start

what has been an annual tradition for me ever since. Young viewers could

imagine being part of the Peanuts gang. In fact, the entire concept is from the

child’s point-of-view with nary an adult in sight.

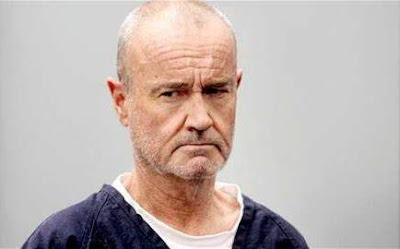

Robbins

performed the role not just in A Charlie

Brown Christmas and It's The Great

Pumpkin, Charlie Brown, but also in the TV specials, You're in Love, Charlie Brown (1967), He's Your Dog, Charlie Brown (1968), It Was a Short Summer, Charlie Brown (1969) and A Boy Named Charlie Brown (1969). In the

1960s, Robbins essentially was Charlie Brown and the unique quality of his

voice virtually defined the role and became the standard by which all later performances

were compared.

Given Robbins’

mental health issues, there is perhaps some irony in a scene early in A Charlie Brown Christmas where Charlie

sits down to discuss his ambivalent feelings about the holiday to Lucy’s 5-cent

psychiatrist. How often, I've thought, did Robbins meet with a court-ordered or

prison psychiatrist and wonder if he could get his five cents back.

Downtown

Charlie Brown

There is a

certain melancholy to A Charlie Brown

Christmas. Charlie Brown is somewhat of an outcast, alternatively rejected

and pitied by the rest of the gang. Even his dog, Snoopy, doesn’t respect

him.

The equally

classic soundtrack by Vince Guaraldi has an overall melancholy feeling to it as

well. Despite the bouncy “Linus and Lucy,” which became the Peanuts

theme, and the ebullient “Christmas

is Coming,” it is largely a reflective work in tone. The other

key original composition for the soundtrack, “Christmastime

is Here,” is wistful, almost somber. Though singing of Christmas

Present, it seems more like a vision of Christmas Past, or a Christmas one

wished for, but never happened.

| A Charlie Brown Christmas soundtrack album by the Vince Guaradi Trio on the Ae13U Sounds YouTube channel. |

At the heart of

the storyline in A Charlie Brown

Christmas is the Christmas tree. Tasked with buying a Christmas tree for

the play, Charlie Brown purchases what is essentially a sickly and rejected overgrown

twig and immediately identifies with it. The tree is not only a stand-in for

Charlie Brown, but also for the Christ Child, who entered the world poor, born

in a manger, and befriended by shepherds and magi who brought his family gifts.

In short order, A Charlie Brown Christmas quickly became

recognized as the apex of children’s animated Christmas specials. Its message

has transcended not only generations, but also religions as people of all

creeds, even atheists, have come to appreciate its timeless message.

One can also not

ignore Robbins’ contribution to its success. Though only nine years old, he

successfully manages to convey the range of emotions from concern, disappointment,

depression, and despair to empathy. It is a remarkable, underrated performance.

Because A Charlie Brown Christmas and

It's The Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown,

are among the most popular of such TV specials, Robbins’ performances will

likely endure as part of the holidays for as long as they are celebrated.

|

| A young Peter Robbins, middle, with director Bill Melendez, far right, and other child voice actors recording for a Charlie Brown special in 1968. |

The

Low-Down on Brown

The Peanuts characters

are archetypes of children one encountered in their own neighborhoods. Everyone

at some point in their life knows someone like or can identify with one of the

gang; however, it is the put-upon Everyman, Charlie Brown, that centers the

strip — the ever hopeful, lonesome loser who always comes in last. The guy who

has the football taken away from him at the last moment when he goes to kick

it, and then gets up to try again and again.

I sometimes

think we enshrine Charlie Brown’s and similar downtrodden characters’ “keep

trying” attitude to alleviate our guilt over the zero-sum calculus of society.

For everyone who succeeds, someone fails. Someone gets a bag filled with candy,

another gets rocks. We need Charlie Browns to keep trying because while we

believe in the inherent inevitability of our success due to persistence, we

fear life is still pretty much a crap shoot.

For anyone, the

burden of that legacy would be heavy. For Robbins, born with a bipolar

disorder, it was overwhelming. Yet, where does one go after peaking at the age

of nine? This is the terrible inheritance for child stars who were part of

iconic film and TV shows, like Anissa Jones (Buffy on Family Affair) discussed in my post “Family Affairs and Pieces of Our Childhood.”

The burden of

Robbins’ bipolar condition led to alcohol, drug, and sex addictions, as well as

obsessive behavior, stalking, threats of violence, and manic episodes. He did

two stints in prison totaling more than five years where he suffered beatings

from other inmates and put in isolation. When I worked in prisons, I once

visited the secure holding units (SHU) at a maximum-security facility. It was a

circle of hell. The thought of Robbins there, battling his own mental illness,

fills me with a deep and profound sense of sorrow and tragedy.

When once

parents struggled with how to tell their children there is no Santa Claus, they

can now add to the list when to tell them Charlie Brown committed suicide.

Somewhere, I

imagine Robbins is with all the other tragic former child actors, becoming

something of a celluloid version of Peter Pan and the Lost Boys — eternally

young, at least on film. Robbins, like the Ghost of Christmas Past, through his

final act, is fated to return every year as a slightly bitter aftertaste to A Charlie Brown Christmas, reminding us

of loss and tragedy every December.

Perhaps it

can also teach us to better appreciate the forgotten Christmas trees in the

world that can still grow and thrive with just a little bit of love.

● ● ●

Once again, Aeolus has resurrected the Underdog - sorry Snoopy - to remind us of his enduring meaning and relevance to humanity. Charlie Brown was indeed a mirror of the 60's. Well done, enjoyed the article. Thank you Peter Robbins, rest in peace.

ReplyDeleteThank you for reading and your kind words!

Delete